Subscripe to be the first to know about our updates!

The Time has Come for a New EU Strategy for Turkey

Mehmet Efe Çaman

Cooperation and Integration, two carrots of the European Union, are considered influential and effective policy tools that enable the transformation of candidate and associated countries. In this context the EU contributes to peaceful coexistence in Europe and its neighboring regions and promotes economic and political stability, prosperity, democracy, human rights and the rule of law across Europe. Many countries rode the wave of European integration for their democratization and stabilization such as Greece, Spain and Portugal in the southern enlargement of the 1980s and all Eastern European countries after 1989.

Turkey’s participation in the European integration process dates back to 1959 and includes the Ankara Association Agreement (1963). Turkey applied for EU membership in 1987, established a customs union with the EU on the basis of the Ankara Agreement in 1995 and was officially declared eligible to join the EU in 1997. As of 2005 Turkey had fulfilled the EU requirements. But as democracy research confirms, democratization is not a static process. Turkey no longer sufficiently meets the EU’s political criteria for accession. Turkey’s ultimate foreign policy goal to become an EU member was a powerful external dynamic that initiated a comprehensive system transformation in Turkey.

In July 2017 the European Parliament called for a suspension of Turkey’s EU negotiation process, referring to the Turkish regime’s crackdown on its opponents.

UNDERSTANDING THE DECLINE and eventual collapse of Turkish democracy is no piece of cake. Turkey’s domestic power constellation is complex and volatile. The key in this constellation is civilian-military relations. The military was the guarantor of the unitary state that socially engineered a Turkish identity as the foundation of a Turkish nation-state. It aimed to diminish all ethnic identities other than Turkish.

During Turkey’s long European journey, the EU considered the special role of the Turkish military in the Turkish political system as an anomaly and asked Ankara to normalize civilian-military relations (to subordinate it to the elected government). In other words, the limitation of the power and influence of the military was a key condition in becoming an EU candidate country and very much in the interests of Erdoğan’s Islamist agenda. Using the EU reform process to democratize the constitutional order in Turkey was the only way to convince the pro-secular and Kemalist establishment (military and bureaucracy). The pro-EU and pro-Western wing of the Turkish establishment (the dominant faction) agreed to this idea and gradually accepted the normalization process, which ended up subordinating the military to civilians. Back then the Erdoğan government was pursuing a liberal Kurdish policy, officially conducting negotiations with Kurdish separatists to end their long-standing bloody conflict. While moderate soldiers accepted this policy, another faction in the military disagreed with it because they believed the EU accession process of Turkey and the political reforms associated with it (particularly minority rights related to Kurdish politics) would eventually lead to dissolution of the unitary Turkish nation-state. Some high-ranking members of this faction planned a coup to overthrow the government and were subsequently arrested. The following (Ergenekon) trials resulted in lengthy prison sentences for most of the accused officers.

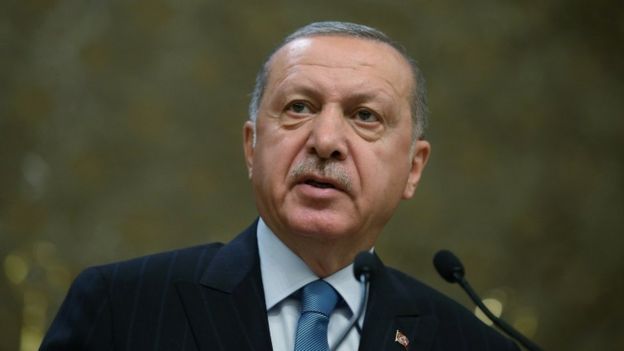

Nevertheless, in 2013 Turkey was shaken by a massive corruption scandal that reshuffled the deck and changed the political power balance in the country. The power vacuum created by this scandal could have cost then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his inner circle their political careers, if not put them in jail. Erdoğan had to stop the ongoing judicial process to ensure they faced no criminal or political consequences. However, he was not influential enough to control the judiciary. The urgent help he needed came from the deep state. In return, according to the expectations of his allies, Erdoğan publicly terminated the “Solution Process” with Kurdish separatists and declared that the criminalization and detention of soldiers in the Ergenekon case was a plot organized by the Gulenists. All the evidence against Erdoğan and his inner circle was declared fake; judges, prosecutors and police officers involved in the criminal investigation were unlawfully discharged, and official investigations into the corruption scandal were swept under the rug.

THIS WAS A CIVILIAN COUP by Erdoğan and his allies. It extended Erdoğan’s power and enabled him to control the judiciary. Erdoğan’s name was now cleared, and the deep state had the upper hand. After the military coup attempt of July 15, 2016, the most comprehensive liquidation in the republican history of Turkey took place. About 50 percent of all flag officers in the Turkish military and thousands of other high-ranking officers were jailed. The officers who opposed the Turkish military’s pro-EU course were appointed to key positions in army, navy and air force command structures.

After the new regime was established and Erdoğan gradually increased and consolidated his new coalition’s power, he pushed a so-called “presidential system.” This should not be confused with the American or French systems. In this political system, Turkey is now undoubtedly an autocracy that is entirely detached from Western or European standards: no independent judiciary, no free press and no free civil society. Most scholars agree that Turkey is now in the club of “strong rulers” along with Russia and China. The Turkish presidential system, which has no checks and balances, is entirely incompatible with the EU’s core values. Moreover, through this system, Erdoğan could hypothetically stay in power for a very long time. With the new presidential system, he can run twice and also for a third time if he calls for early elections. And calling early elections is within the president’s authority.

The new regime’s ideology and the official discourse based on it serve to consolidate the regime. It is a matter of hybrid ideology, a mix of Islamism and Turkish nationalism in which the latter is more dominant. The new ideological amalgam of Islamism and Turkish nationalism is extremely anti-West and anti-EU. Erdoğan uses this ideology at every opportunity and declares the EU (and the West) responsible for any failures. The new perception of Turkey’s political elites portrays Europe as a fortress of Nazism that is anti-Turkish and anti-Muslim and wants to weaken Turkey. Relations with the United States are at a low point because of Turkey’s decisions to launder Iranian money and support Iran’s dubious nuclear program, to buy S-400 missiles from Russia (a huge area of conflict with the United States and NATO), and to use foreign prisoners as bargaining chips under the cover of a remote-controlled judiciary in the orbit of the regime.

While this power shift occurred in Turkey and a de-facto regime emerged, the EU preferred a wait-and-see policy. Europeans were undecided regarding the future of Turkish-EU relations and particularly about Turkey’s membership, anyway. Turkey was too big, too poor and too Muslim. Beyond the formal membership perspective and the standard bureaucratic negotiation process, there was no particular motivation in the EU to give Ankara the trajectory that would lead to EU membership. Fixing Turkey’s troubled democracy was simply too “normative-ethical” and might underline serious material interests such as bilateral trade relations. This undermined the EU’s credibility in Turkey and empowered Erdoğan and his new allies’ de-facto regime. Beyond this, the EU members and the union itself were experiencing the biggest refugee crisis since World War II. Millions of Syrians fleeing the civil war came to Turkey with the hope of traveling further west and northwest to Europe. The tragedy of asylum seekers who lost their lives in the Aegean Sea garnered the attention of the international community, which forced the EU to address the issue. However, the response from the EU was not to secure the refugees’ passage to the EU but rather to send them back to Turkey.

THE REFUGEE DEAL, signed in March 2016, promised Turkey aid, visa-free travel for Turkish citizens and accelerated EU membership talks in return for stopping the Syrian refugee influx to keep Europe as refugee-free as possible. As a result, Turkey has become the biggest EU refugee camp. Since the deal, Erdoğan has used the existence of 3.5 million Syrian refugees in his country to blackmail the EU and its member states. He repeatedly threatens EU countries with allowing refugees to travel from Turkey to Europe whenever the political climate between Ankara and Brussels deteriorates.

What can the EU do? Some EU officials believe that freezing accession talks with Turkey would feed the Islamist-nationalist narrative. However, the ongoing pathetic “wait-and-see policy” of the EU based on the refugee deal with Erdoğan and some other short-term interests are factors that only strengthen the regime. It is unlikely that anyone in Europe’s capitals has ever believed that this strategy would function, anyway. It was just an official narrative to justify the passivity of the EU’s Turkey strategy. The EU never prioritized a strategy based on normative politics such as supporting Turkey’s political normalization process in terms of restoration of the constitutional regime, the rule of law, individual and minority rights, etc. Turkey is a country with no oil or gas, low savings in relation to GDP and is in need of daily short-term borrowings and long-term foreign direct investment. Turkey’s current economic crisis has been caused primarily by the regime’s mismanagement – unmaintainable borrowing, nepotism and huge public construction projects with little economic return. The devaluation of the Turkish currency cannot be stopped, continually driving prices higher in the country.

The EU is still a vital partner of Ankara in trade, borrowing and investment. Turkey needs to improve the existing customs union and deepen its economic dialogue with Brussels more than ever before. Turkey-EU economic relations are deeply institutionalized, and they can only continue if Turkey functions as a transparent rule-of-law country. It is time for the Erdoğan regime to realize that the EU’s carrots only rest on rule-of-law-based governance. However, Erdoğan has noticed that the EU hesitates to combine carrots with sticks, which undermines the influence of Brussels in Turkish domestic politics.

Therefore, the EU should not stand still while Turkey backslides on democracy. Without a credible EU conditionality, both Turkey and the EU will lose in the medium and long term. What the democratic forces in Turkey need is a new EU strategy for Turkey that is based on this conditionality. But for a new EU strategy to be formed, the old one must first be terminated. This requires a return to normative EU politics on Turkey, emphasizing the restoration of the constitutional regime, the rule of law and individual and minority rights: in a nutshell, the re-democratization of Turkey. To achieve this, the EU should freeze the negotiation process, with a clear evaluation of Turkey’s political situation as soon as possible without losing any time and promise a democratic Turkey a real membership perspective to revitalize the pro-European and democratic domestic social dynamics in the country. Otherwise, the EU will lose Turkey.

Source; Turkish Minute