Subscripe to be the first to know about our updates!

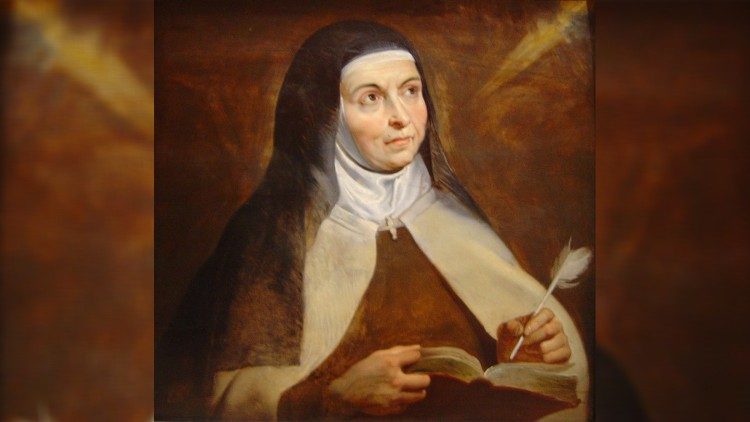

St. Teresa of Avila

Alaa Alghamdi

What is immediately evident from reading the life story of St. Teresa of Avila is that she was a headstrong woman who was never content to embrace the status quo, but always wanting to challenge it and her role within it. The stories that caught her imagination when she was young may bear little relation to her actions as an adult, forming convents according to an ideal of poverty and humility, but they both seem to point to an aspiration to something other than the life that was generally afforded to a young woman in her position. As a child, she was inspired by the stories of the saints and wanted to run away and become one. Later, as a teenager, she was inspired by stories of chivalry – a very different, secular form of heroism. It is possible to view her later work, her formation of austere convents in reaction to what she regarded as a degraded religious life that currently existed, in the same vein. She was heroically conquering something that she found lacking in the world. Her willingness to go to unusual extremes – the extent of the poverty of the nuns in the convent she originally founded, and the fact that they were without shoes – may point to a passion for transcending the boundaries and limitations of what was considered usual or normal in her world and entering what is indeed a sort of heroism or at least a type of extreme behavior and a worldview the certainly transcended the commonplace.

Teresa of Avila was convinced that Christ had appeared to her in physical form; her theory of the progress of the soul includes an ecstatic union with the divine which transcends reason and ordinary life or perception. She was, in both a philosophical and actual sense, a transgressive figure. Using her transgression in the cause of holiness and increasing closeness to the divine through deprivation of worldly goods was perhaps what made it acceptable to the (highly religious) society of her time. Her religious orientation was certainly in keeping with and acceptable to her community. Furthermore, it was far more palatable, perhaps, for a woman to want less – less luxury, fewer worldly possessions – than to want more in any sense. However, we can also surmise that Teresa did indeed want ‘more’ – unsatisfied with the state of the social conventions surrounding religion, she made them more extreme. She built for herself and those around her an alternate reality where life is lived according a set of rules aimed to block out the everyday world, and communion with the divine is a daily occurrence. In other words, she lived inside an altered consciousness (even when not having visions) and manifested it outward, responsible for the establishment of 17 convents according to her principles as well as a corresponding number of male institutions.

Manifesting one’s personal vision outward into the world is perhaps a version of empowerment that goes beyond mere agency, the power to act for oneself within existing structures. Teresa manifested what was in her head and heart and it was built into a reality. However, it must be noted that she did so in perhaps the only arena that was open to her, as a woman of her time and place. The enterprising spirit was evident within her since she was very young, and the convent was her only available forum to express it.

Professor of English Literature *